The cPanel, or control panel, is your landing page for University of Rochester that lets you easily access and manage the files and applications of your account. Once logging into your account, you can see your active domains and personal account information at a glance.

Applications

University of Rochester has four featured applications listed, but there are many, many more that can be utilized. Just click on All Applications in order to see what possibilities lie in wait for your domain! For more information about web applications, click here.

Domains

The Domains section of cPanel allows you to manage your addon domains, subdomains, aliases, and redirected domains. Additionally, you can use the Zone Editor to map different parts of your domain to other hosting environments.

-

- Addon Domains act as second website with its own unique content. Please note, you are required to register the new domain name before you can host it. Reclaim Hosting, our hosting provider, offers a service for this, although there are other domain registration companies if you’d prefer to look elsewhere.

- Subdomains act as a second website with its own unique content without having to register a new domain name. In general, you use your existing domain name and change the www to another relevant term. For example, student.digitalscholar.rochester.edu is a subdomain of digitalscholar.rochester.edu.

- Redirects map old domains to your existing domain.

- Aliases allow you to create additional domain names to be mapped to the current domain.

- Zone Editor handles DNS (Domain Name System) and allows you to see what’s happening behind the scenes when someone visits your website. For more information, see the “What is DNS?” section of this documentation.

Files

Within files, you are able to manage and organize all the files on your domain. To truly see the capabilities of these tools – just click and explore!

-

- File Manager allows you to manage all files connected to your account, including renaming, uploading, and deleting them. You can also get to your file manager using the Quick Links section at the top left of your cPanel.

- Images lets your manage images that have been previously saved to your account.

- Directory Privacy allows you to set a password to protect certain directories of your account.

- Disk Usage helps you monitor your account’s available space.

- File Transfer Protocol (FTP) is a fast and convenient way to transfer large files online. More information can be found in the “Setting up FTP” section of this documentation.

- R1Soft Restore Backups is the recommended backup option of the three backup icons displayed. You can read more about it under the “Automated Offsite Backups” section of Reclaim’s blog post “Backups Done Right”.

Databases

The Databases section allows you to create MySQL and PostgreSQL databases and users, and to modify and access to them. SQL stands for Structured Query Language. SQL is an international standard in querying and retrieving information from databases. PostgreSQL is an object-relational database management system.

-

- phpMyAdmin: manages a single database as well as a whole MySQL server.

- MySQL Database & MySQL Database Wizard: allows you to store and manage large amounts of information over the web; these are essential to running web-based applications, for example: bulletin boards, content management systems, and online shopping carts. The Wizard guides you through the setup of a MySQL database and user privileges.

- Remote MySQL: You can use this to add a specific domain name so visitors can connect to your MySQL databases.

Metrics

cPanel offers a number of different monitoring and statistic tools to help you administer your hosting account. Some of the more important and useful functions are explained in more depth below.

-

- Visitors: Use this to see your 1,000 most recent visitors for each of your domains.

- Errors: This displays the last 300 errors on your site; helpful if looking for missing files or broken links.

- Bandwidth: Bandwidth represents the amount of information that your server transfers and receives. Use this function to view the bandwidth usage for your site; see total usage, or by month. Includes web and mail usage.

- Raw Access: This is another stats function that allows you to see who has visited your website without graphics. A downloadable zip file of your site’s activity is availble.

- Awstats: Allows you to see your website visitors with visual aides.

- CPU and Concurrent Connection Usage: Lets you visualize the CPU and RAM usage of your site.

Security

cPanel has an entire security section devoted to protecting different parts of customer web sites from the unauthorized access of their viewers. The cPanel Security section includes SSH Access, IP Blocker, SSL/TLS, Hotlink Protection, Leech Protection and ModSecurity.

-

- SSH Access: Allows secure file transfers and remote logins online. Watch a video on how to manage SSH Keys on Reclaim Hosting.

- IP Blocker: This function allows you to block a range of IP addresses to prevent them from accessing your website. This is done by simply searching a qualified domain name.

- SSL/TLS: The SSL/TLS Manager will allow you to generate SSL certificates, certificate signing requests, and private keys. These are all parts of using SSL to secure your website. Information is sent encrypted instead of in plain text.

- Hotlink Protection: Prevents other websites from directly linking to files on your website.

- Leech Protection: Prevents your users from giving out or publicly posting their passwords to a restricted area of your site

- ModSecurity: Protects your website from various attacks using a web application firewall, provides additional tools to monitor your Apache web server.

- SSL/TLS Status: Allows you to view, upgrade, or renew your Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) certificates.

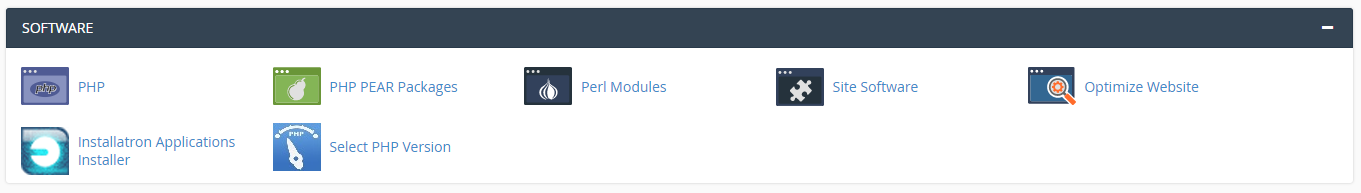

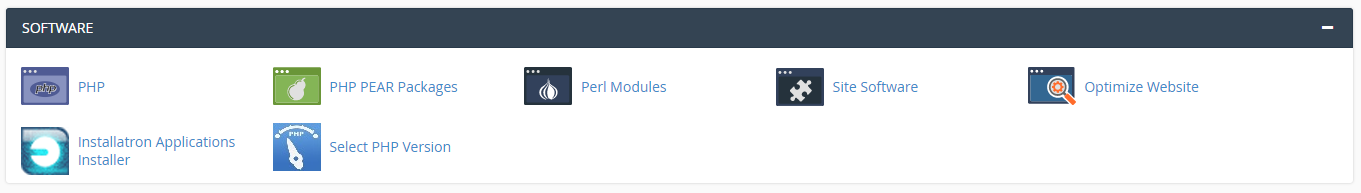

Software

The Software section of cPanel is located towards the bottom of your cPanel dashboard. The functions that get used most often in this category are Optimize Website and the Installatron Applications Installer.

-

- Optimize Website: This function allows you to optimize the performance of your website by tweaking the way Apache handles requests

- Installatron Applications Installer: Another route to the “View More” in Web Applications, which lists all available features that can be installed on your domain.

Advanced

The Advanced Section is located at near the very end of your cPanel dashboard. We recommend using this area only if you are familiar and comfortable with utilizing these features.

-

- Track DNS: this allows you to find out information about any domain; trace the route from the server to your computer, for example. This can be helpful to make sure your DNS is set up properly.

- Indexes: This manager customizes the way a directory can be seen (or not seen) online.

- Error Pages: In two simple steps, you can select the domain you wish to work with, and then create/edit error pages for that site that viewers will see.

- Virus Scanner: is essentially what it sounds like; start a new virus scan in Mail, Entire Home Directory, Public Web Space or Public FTP space.

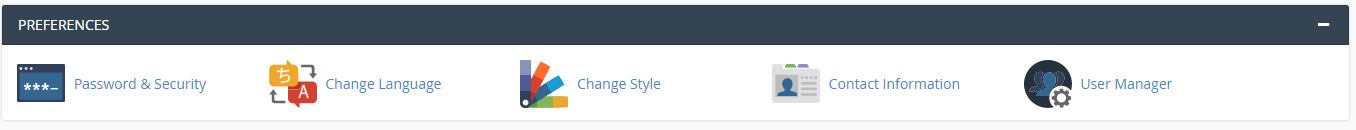

Preferences

The Preferences area allows you to change your language, change the style of the interface, and your contact information. While we recommend that you leave your primary contact email as your school email address, you are more than welcome to add a second! Further, within Contact Information, you can update your notification preferences.